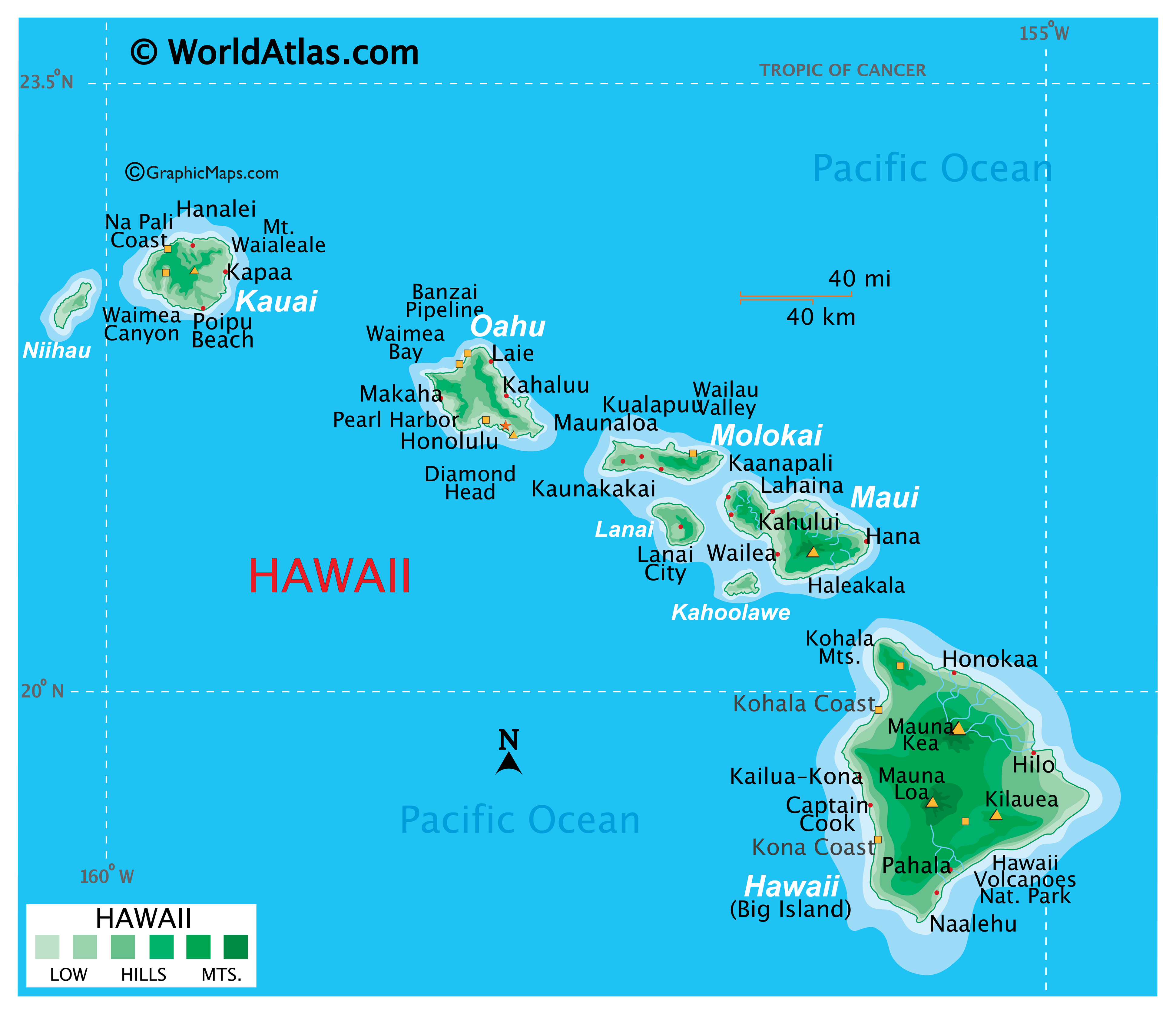

Associated Press recently reported that Maui County, Hawaii is suing several cellular carriers for a failure to notify law enforcement of cellular outages during the disastrous Lahaina wildfire during August 2023. The article can be found here:

Over the years, the author has written several articles intended to deconstruct emergency management failures, including those during Hurricane Katrina, the 9-11 attacks on the World Trade Center, Hurricane Maria, and so forth. The events surrounding the Lahaina fire are typical of other planning and response failures during major incidents.

Perhaps the most obvious of several failures by emergency planners in Hawaii is the assumption that the cellular grid is nearly indestructible. This assumption is somewhat understandable. Our nation’s cellular network is quite robust and, generally speaking, very reliable. This reliability, when combined with the fact that the cellular mobile data network has become an omnipresent and central factor in everyday life, simply makes it difficult for today’s generation to imagine a situation in which it is rendered inoperative. The result is a high degree of cognitive dissonance that impedes hazard and vulnerability analysis.

While the public may be forgiven for their assumption that their cellular service will always be available, the same cannot be said for public safety officials. There are numerous examples of widespread cellular outages during wildfires. Just a bit of research will quickly reveal that the cellular grid has failed during events similar to the Lahaina fire. Just a bit of research will also quickly reveal that “reverse 9-1-1” methods also failed in similar events, including the infamous “Camp Fire” in California several years ago.

The failure to subordinate assumption and personal experience to proper research in the form of an effective emergency management program and the basic requirement of hazard and vulnerability analysis results in misplaced priorities and the adoption of protocols that are inherently flawed. In fact, a variety of alternatives to “reverse 9-1-1” emergency messaging are available. For example, NOAA weather radio receivers can be distributed and programmed to alert residents to “Civil Emergency Messages” warning of a wide variety of local hazards. Hawaii is equipped with an impressive siren network designed to warn of tsunami, earthquake and volcanic activity. It would seem reasonable that the siren system could be utilized to warn of dangerous wildfires.

In recent decades, the FCC and other regulators have abrogated terrestrial radio broadcasting through rampant media consolidation, resulting in poor quality programming, the death of local programming, and the exodus of listeners to streaming services and on-demand content. The result is decreased effectiveness of the Emergency Alert System which, when combined with the lack of 24-hour staffed broadcast stations, results in a far less effective emergency warning process. Yet, terrestrial broadcasting is, if not a far more survivable resource for emergency warning, certainly an additional tool in the tool belt.

Maui county may have also made a mistake by opening the door to the legal process of discovery with this lawsuit. Undoubtedly, lawyers for the defendants will have many questions about the county emergency management program. They will research its effectiveness to determine if the required processes were in place. They will investigate to determine if the political appointees responsible for implementing an emergency management program were qualified. They will examine the emergency action guidelines to determine the extent of stakeholder input….and so on.

It is odd that one finds himself defending the cellular carriers. It’s a bit like cheering on an insurance company in a lawsuit. Yet, numerous counties throughout the United States have no emergency management process or they have an emergency management process in name only. While the author has no direct insight into the effectiveness of the Maui EMA, it will be interesting to see what comes of this lawsuit.

So, what does all this mean for emergency managers and the community of radio amateurs? The take-aways should be obvious:

- The first and foremost responsibility of an emergency manager is the hazard and vulnerability analysis. This process must also be applied to the infrastructure and tools upon which the response phase is built.

- The cellular mobile data networks that are so central to our lives are not invincible. Public Safety agencies should see cellular based communications as a secondary or even tertiary method for both internal communications as well as for public warning functions.

- There is no substitute for basic, two-way radio communications. The fact that cell phones are familiar and comfortable does NOT justify their use as a primary emergency communications tool. Furthermore, cell phones should not be a primary tool for day-to-day operational activities either. Basic two-way radio methods should be utilized for every-day communications so that first responders are comfortable with their use and the operational procedures are engrained and automatic to ensure efficient use of circuit capacity in time of emergency.

- RRI encourages radio amateurs to develop and promote its “National SOS Radio Network” and “Neighborhood Hamwatch” (Neighborhood Radio Watch) programs because cellular networks do fail during major disasters. These RRI programs are an ideal project for radio clubs and EmComm groups. They provide an alternative for community and neighborhood organizations in the event of cellular outages.

Radio amateurs may not be RF systems or network engineers, but most ham operators have a good, general understanding of radio systems and telecommunications networks. We should encourage our public safety agencies to avoid the trap of assuming that cellular networks can serve as the glue that holds disaster response together. They are, in fact, secondary resources.

Attend the RRI “Emergency Communications Planning” course TR-006. This course provides an in-depth understanding of the common factors affecting telecommunications resources during a disaster. It also provides an excellent outline for those responsible for developing an effective emergency communications program.

Lastly, take a good look at your local EMA. Many programs simply exist to fulfill a legal requirement or to obtain funds from a nearby industry or nuclear power plant. Encourage your elected officials to take a good look at program effectiveness. Emergency Management is not a law enforcement function nor is it a technical function as in the case of fire service. Rather, it is a collaborative process designed to ensure a coordinated, effective response without duplication of services. The emergency management director must understand the “big picture.” He or she must also be able to serve as an effective manager of a wide variety of resources. Most importantly, the emergency management director must be able to build working relationships through collaboration rather than compelling coordination through blunt authority.

Emergency response should not be the job of lawyers. It is a collaborative, community-wide effort. Let’s do our part to work toward that goal.